Info about the tool

Purpose: make demonstrable results central to achieving positive changes in social issues

Who is it for: project managers

Technique: co-creation session, interviews

Type of tool: implementation tool

Prior knowledge: little

Complexity: high

Time investment: months and longer

Downloads

Links

Gerelateerde tools

What is Results-Based Accountability?

Results-Based Accountability (RBA), also called Outcome-Based Accountability (OBA), is a method for developing new services or assessing the performance of existing services. This method was developed by Mark Friedman. A distinctive feature of the method is to work from back to front when developing a new service, in other words, the focus of service development is on the results to be achieved by the service.

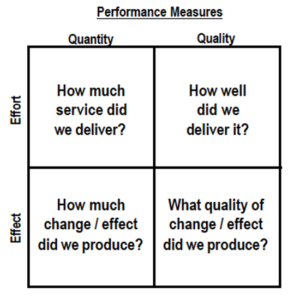

With this method, the premise is to identify the measurable outcomes envisaged. An important process here is what is known as ‘turning the curve’. An estimation is made of how a given metric, such as the number of burglaries in a residential area, will develop if no action is taken. By taking targeted actions, a positive ‘trend reversal’ is envisaged. To assess performance of services, a distinction is made between quality and quantity and between input (effort) and output (effect). The method is also characterised by transparent data collection and utilisation, the use of clear and straightforward concepts that can be understood by everyone, and the involvement of different stakeholder groups to achieve and communicate the results. The maxim here is ‘common language, common sense, common ground’, which is very much in line with the method’s background of bringing about change in the public domain.

How do you use Results-Based Accountability?

Results-Based Accountability (RBA) is a method that can be applied to buck a particular trend (turn the curve) with targeted actions. RBA involves the following steps:

- Determine the target group. For whom do we want to achieve an outcome? Which target group are we talking about? Describe this as accurately and clearly as possible.

- Define the desired outcome. What situation do we want to achieve for this group?

- Determine how the outcome will be measured using indicators. Use the matrix of performance metrics for this purpose (see below). Establish what the goal is relative to the current situation, the so-called ‘baseline’.

- Find out what the story behind the current situation is. What caused the current situation, what is the field of influence and what will happen if nothing changes?

- Identify the key partners; which partners play a role in achieving the intended outcome?

- Think about what will work for this specific situation. Gather examples, suggestions and suppositions to break through the current situations.

- Make an action plan. What will we do, what will it cost and how will we measure how well we are doing?

- Assess performance using the matrix of performance metrics and related questions.

In determining the performance of a given programme, organisation or service (performance accountability), three main questions come into play according to RBA:

- How much did we do?

- How well did we do it?

- Did anyone benefit from what we do?

The actual performance metrics of these three main questions can be mapped according to four types of performance metrics. These four categories emerge by creating a matrix using the concepts of quantity/quality and effort/effect.

The first category of performance metrics relates to the amount of effort expended: how much service did we deliver? This question concerns the quantity of the effort and can be measured, for example, by looking at the number of activities, the budget spent and the deployment of staff.

The second category of performance metrics concerns the quality of the effort: how well did we deliver it? This can be measured, for example, through customer satisfaction scores, percentage of complaints dealt with within an hour and what percentage of the target group is reached.

The main question of whether someone has benefited from the programme or service is the question of its effect, which falls into two categories of performance metrics – quantitative metrics and qualitative metrics. Quantitative metrics answer the question of how much effect has been achieved, for example the decrease in number of accidents caused by alcohol in traffic, the increase in scores on reading tests of children coming out of primary school or the increase in the number of people employed in the creative industries. Qualitative measurements answer the question of what effect has been achieved, for example how happy residents are compared to another region or country, increased sense of safety in a neighbourhood or improvements in customer performance.

Performance metrics tend to be exclusively about volume data, for example the number of customers served and applications processed. Friedman, the researcher who developed RBA, instead makes a case for the quality of performance and considers those quadrants in the matrix to carry more weight. The key performance metric is that of the qualitative effect achieved, which is often the most difficult one to articulate. A helpful way to think about this is to ask the following four questions: Have skills changed? Have attitudes changed? Has behaviour changed? Have circumstances changed?

For Friedman, it is important to measure a few performance metrics regularly and consistently rather than many at once. This provides a more realistic picture of the actual performance achieved. It is therefore essential to choose good performance benchmarks. Three criteria can be used to this end:

- communication power; is the indicator easy to communicate to all stakeholders?

- proxy power; is the indicator a good representative of other indicators so that a total of two to three indicators will suffice?

- data power; is sufficient data available that is valid and reliable and also regularly available to monitor progress over time? By answering these questions with high – medium – low for each possible performance measure, a considered choice can be made.

What is the origin of Results-Based Accountability?

This method (RBA) was developed by Mark Friedman. Initially designed to measure the effectiveness of programmes in the public domain, RBA has also gradually become an approach to catalyse change, such as in education (‘children are ready for high school’), safety (‘clean and safe neighbourhood’) and employment (‘neighbourhood residents have good jobs’). The method is used by local and central governments, but also in projects such as redevelopment of the port of Rotterdam and programmes within the cultural sector. The guiding question in RBA is whether someone is better off – in terms of wellbeing – because of the programme deployed and what social impact has been achieved. However, given the relatively general nature of the principles Friedman uses to map performance, the RBA method can also be applied outside the context of the public domain.